Image credit: Pixaby\qimono

Circular Economy has become a familiar buzzword over the last decade, and more recently we observe a range of definitions developed to describe it. A research conducted in 2017 found that there are 114 definitions to describe a circular economy in the research literature. The question is which is legitimate and which is not. Let’s first explore the ideas proposed by the major proponents of the circular economy.

Schools of thought and concepts embedded in the idea of a circular economy

Ellen McArthur Foundation, a not-for-profit organisation that globally advocates principles of a circular economy, states that there are seven schools of thought that have contributed to shaping the concept .

Each of these represents different principles, some relating to material or nutrient flows, while others relate to economic systems thinking. We can also note some contradictions among these principles themselves. In addition, there are a couple of other economic concepts that complement the thinking of a circular economy.

- De-carbonised economy – where the economy is organised to achieve lower greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions indicated by GHG emissions per unit economic value.

- De-materialised economy – where the economy is organised to lower the amount of material consumed indicated by material consumption per unit economic value.

In a nutshell, the current discussion around the circular economy has a few embedded concepts incorporated into it, which contain different goals.

So, what is the core concept or is it a combination of all these?

And most of all, do they have a converging purpose?

An easier way to understand the concept of the circular economy is to revisit the fundamentals to understand the base.

Explaining from the perspective of material (nutrient) flows

Cradle to cradle principle (C2C) has set the foundation for all principles now communicated associated with a circular economy, yet later modified or interpreted differently. To understand it better, we refer to its purpose, vision, and mission.

Going by “Purpose guides you, Mission drives you, Vision is what you aspire to be”…

1. Core purpose

The distinctive purpose of a circular economy drills down to nothing other than “enabling regeneration”. Based on C2C, and to be more specific “enabling regeneration through addressing upstream activity design” is at its core.

Let’s differentiate where the difference should be made.

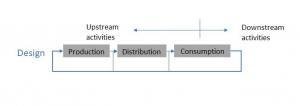

If we make consumption a reference point, the activities prior to consumption are referred to as upstream activities and the processes following that to bring post-consumption resources back to the economy are called downstream activities.

2. Vision

The vision or the state to be, for a circular economy is that all products and services are designed to regenerate through a defined nutrient pathway either via biological or industrial cycles.

C2C talks about celebrating human footprint rather than apologising for it, as increased consumption will nourish the earth if products and systems are defined in line with that. So, consumption can actually be guilt-free, as long as the designed nutrient cycles do their job.

3. Principles

Cradle to cradle has three main principles that it identifies with.

- Resources: Nutrients are nutrients : All resources to be nutrients in circulation. They either belong to a biological cycle or an industrial cycle.

- Energy: Use of renewable energy : Produce energy as renewable energy not through depleting resources.

- Support diversity : The complexity of natural biological systems, as well as economic, social, cultural systems, are to be embraced, appreciated, and celebrated for their uniqueness. Devising context-specific solutions are encouraged.

4. Strategies/ Course of action

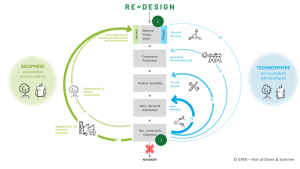

There are specific strategies for the biosphere and technosphere, to define ‘how to do it”.

For the biosphere, regeneration can happen through industrial or natural processes to add the nutrients back to nature.

For the Technosphere, the strategies are:

- Share (products)

- Maintain (products)

- Reuse (products)

- Repair (products)

- Refurbish (components )

- Remanufacture (components )

- Upcycle (materials)

- Recycle (materials)

Adopted from: https://epea.com/en/about-us/cradle-to-cradle

Recycling is the 8th strategic priority, which might be a little alarming, yet it is the last resort in a world where regeneration is made possible.

If Cradle to Cradle principle is understood correctly, “recycling materials to form a closed loop” or “achieve circularity by recycling” is truly not the underlying message. A number of strategies need to be employed to redesign upstream activities (production, distribution, and consumption) so that a reverse nutrient flow is achievable. In fact, the focus should be on optimally designing the upstream, rather than sub-optimally modifying downstream activities to achieve regeneration of nutrient flows.

An economy generating waste and requiring it to be recycled and repurposed at a material level is a linear economy, as waste is a strong signal that ‘designing upstream to regenerate nutrients’ have not or sub-optimally taken place.

Why can Cradle to Cradle be considered a clear and integral way to explain a circular economy?

Cradle to Cradle principle talks about optimum product, component, and material strategies and the use of renewable energy as the ideal case. Therefore, regeneration of products, components, and materials are optimised in the strategy hierarchy itself.

As an example, a gold jewellery item would explore the first six strategies in the industrial cycle before it is remelted to make another product when none of the six strategies at the top require energy-intensive material modification processes.

Attempts to make waste flows circular can create worse outcomes

Waste materials, which is a by-product of a linear economy, may need high energy for resource-intensive recovery and repurposing processes to reinstate it to form a closed loop. If the principles of regeneration are achieved at the cost of resources and energy, they can produce contradictory outcomes, where there is a trade-off between “decarbonising” and “regenerating”.

For example; let’s take a quick look at the process of concrete recycling. Once concrete waste is crushed, it typically separates into several constituent streams – coarse aggregate, fine aggregate, steel pieces, etc. If we separate the coarse aggregate portion that contains residue mortar from concrete and take it through a heat treatment process or a series of cleaning processes to remove mortar on the surface of the aggregate so that the resultant product is similar to natural coarse aggregate, theoretically you can achieve circularity or a closed-loop. However, a life cycle assessment (LCA) result is likely to suggest that the environmental impact of relevant categories (such as Global Warming Potential) is reportedly high, with high consumption of energy.

Repurposing has its own costs – we need to be objective to see them

Resource and energy use generating further waste and undesired by-products, are other likely outcomes of recycling to achieve “purity”. Minimising energy and resources often end up with a “downcycled” ingredient, which would add complexity to a different product stream. All these negative consequences are a result of sub-optimally designed product in the upstream.

This form of regeneration is not the essence of a circular economy.

Solutions in line with a circular economy would be – either to, design the materials in the concrete mix to enable recovery of some components (remanufacturing and designing for recycling), replacing concrete with a material which is more regenerative (upcycling) in buildings, or changing the way buildings are built and sold (Sharing).

Using circularity as a “goal” or “strategy” in repurposing waste (downstream processing) can often lead to worse environmental impacts. Even for upstream process design, circularity does not necessarily mean restating to original condition, but to be regenerative into multiple cycles enriching the environment rather than depleting it.

How far away are we from being “circular economy – ready”?

Being in a linear economy, we do generate waste currently and seek alternatives better than landfilling and incineration.

When recycling stands as the next best alternative, it is important to measure those with absolute environmental impact indicators such as Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). A comparative LCA would provide an idea of the resource and energy consumption associated with recycling to regenerate materials. The decision to replace a traditional material with a waste-derived material is a multi-criteria decision involving cost and performance aspects in addition to the environmental impact. There is also the need to make a call on whether the repurposing complicates a simple material cycle, in which case a bigger problem remains to be addressed in the next generation of the product when its end of life is reached. There are a series of “due-diligence” questions to ask to qualify solutions that lead to reduce impact than to worsen it.

Above all, rather than considering ‘circularity’ or ‘closed-loop’ status achieved as a win, it is important to acknowledge that we are in a linear economy if we are repurposing waste.

Measurement criteria

If we go back to the base, Cradle to Cradle adopts measurement criteria employing five aspects to qualify and rate products. The “ability to regenerate” and “consumption of energy” is captured in the second and the third criteria, whereas the first criterion focuses on “material health”, i.e., removing toxic and complex compounds from product chemistry to make the end of life management simple.

Transitioning from a linear economy to a circular economy is complex and not knowing what to aim at to implement small transition actions can be daunting. Setting a roadmap for high-level transformation and implementing a phased transformation with goals addressing the key fundamentals would be a better approach to take. Measurement of where the alternative stands compared to the current practice is absolutely important, to avoid creating a worse outcome.

This article is one of a series of articles that we will use to discuss different concepts, principles, and strategies associated with a circular economy, compare and contrast them, point out where their validity and contradictions lie as well as discuss common myths around the concepts.